In the Absence of War: Giving Peace a Chance in Northern Ireland

by Kathleen LaCamera

Response Magazine – September 2003

In the wake of recent celebrations marking the end of World War II in Europe, it’s tempting to imagine that one day a war can be raging and the next day the guns go silent and peace breaks out. It took years to rebuild Europe to the point of economic, political and social stability that made for real peace. In the US we forget that civilian rationing of food and other goods continued in Europe well into the 1950s. Northern Ireland today, like Europe after World War II, needs time, resources, and committed determination to build a meaningful peace.

In the wake of recent celebrations marking the end of World War II in Europe, it’s tempting to imagine that one day a war can be raging and the next day the guns go silent and peace breaks out. It took years to rebuild Europe to the point of economic, political and social stability that made for real peace. In the US we forget that civilian rationing of food and other goods continued in Europe well into the 1950s. Northern Ireland today, like Europe after World War II, needs time, resources, and committed determination to build a meaningful peace.

Northern Ireland is now relatively free from the armed violence between Catholics and Protestants that has plagued this region for decades. There are official ceasefires and signed peace agreements in place. Military check points have been dismantled. People report life is tangibly improved. Even so it is hard to identify the current climate where hard line sectarian politicians win elections over more moderate Nobel peace winners and marginalized young people see vigilante style paramilitary groups as a viable career choice, as one in which peace truly has arrived.

The congregation of the Methodist East Belfast Mission lives with the fall out from sectarian conflict and neglect every day. Located in a heavily Protestant working class neighborhood of East Belfast’s Newtownards Road, the mission serves area known as one of the worst places to live in all of Northern Ireland. The towers of the Harland and Wolff shipyard nearby are a painful reminder of prosperity and opportunity that has drained out of their community over years of violence and economic decay. In its heyday, the shipyards employed as many as 40,000 people. Today less than a hundred jobs remain. The area also has strong links with Protestant paramilitary groups which continue to wield power and influence over the community.

The mission’s minister, Gary Mason, says it is all too easy for people in his community to focus on the past and what has been lost, rather than risk hope in a new and unknown future. Huge paramilitary murals glorifying Protestant “freedom fighters” remain a prominent feature of many buildings along the main road.

“You drive down the streets here and it’s a wasteland, explains Mason. “It’s all shops with steel doors across them, locked up tight. There’s no reason to stop.”

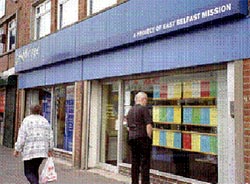

Working to overcome the cycle of despair, isolation and deprivation that has taken hold here, Mason and his mission team are trying to make the “peace dividend” a reality for this community. Over a number of years and in partnership with a variety of churches, community groups and government agencies, the East Belfast Mission has worked creatively, painstakingly and doggedly on many fronts. It operates a homeless shelter, a job center and a day center for older people. There are groups for mothers and babies and outreach to parents finding it hard to cope.

The mission’s ambitious Skainos Project includes plans to develop a two acre site creating a full scale community center with program and meeting facilities, a café, gardens, even commercial store fronts. “Skainos” is the Greek word for “tent.” The project aims to pitch a broad tent in the midst of East Belfast offering welcome and practical support to the whole community. Both Catholics and Protestants serve on the board overseeing project. Mason believes this kind of home grown regeneration is essential.

“The peace process and the funds that have come into Northern Ireland with it, has worked for my family, for the middle class,” said Mason. “But for the people in the inner city, they haven’t felt tangible results from the peace dividend.”

In a recent development, Skainos has formalized a partnership with the Belfast Institute of Higher Education with the goal of offering retraining and job placement to those making a transition out of paramilitary activity.

Mission outreach worker Glen Jordan explains that in order to get these “ex-combatants” to disband, disarm or alter their existence in some way they need access to education and retraining.

“The real issue is to get them jobs and to help them provide for their families,” says Jordan.

For years, paramilitary members have enjoyed status, purpose and power in their community that isn’t easy to leave behind. Jordan recounts one encounter with a paramilitary commander who said, “when this ends my men will not go into community work. We’re not interested in helping old ladies, we’re soldiers.”

While many Catholic paramilitary members have turned to politics and community organizing, Protestants haven’t, feeling the official political process has let them down badly.

“How do you deal with people who still see themselves as soldiers?” asks Jordan. “The danger for us if we don’t find productive ways to re-engage these ex-combatants is that they will move to gangsterism.”

Fortunately these are questions which some paramilitary members themselves are asking. In another initiative spearheaded by the mission several high ranking paramilitary leaders travelled to Munich to look at the legacy of sectarian intercommunity violence and racism of Nazi Germany against the Jews. Jordan, who travelled with the group, reports that it took very little time for those present to make links back home to their own destructive sectarian conflict.

“They began to question their own involvement in the paramilitary community,” said Jordan. Conversations continued late into the night about costs of paramilitary involvement for their families, their health and their personal aspirations. The group also voiced real concern about the “militarism” of the next generation of younger men coming up and a future for their community.

“It was a profound six days,” says Jordan.

Aware of the real dangers of the next generation becoming caught up in the legacy of violence, the East Belfast Mission has put significant resources into work with young people. Three years ago the mission bought a pub and transformed it into a youth club facility called Luk4. The club runs a range of activities for young people, many of whom are vulnerable to the worst of local paramilitary influences. The United Methodist Church Board of Global Ministries helps fund missionary Linda Armitage who, as the mission’s Youth and Community Director, coordinates Luk4 along with projects.

Teaming up with Glen Jordan, Armitage involved Luk4 young people in creating stories, poetry, films, photographs that tell the story of their experience of life along the Newtownards Road. The result was a successful photographic exhibition entitled “Night News” which eventually became a book.

“These kids were coming into the art exhibition saying ‘I did that’, ‘look what I’ve done,’” remembers Armitage. “If we want people to think outside the box, they need to be stimulated creatively. This experience enables participants to value their own life experiences.”

“Art has been used as a political football in Northern Ireland to make political points. We want to use community art as a way of redeeming art here; as a way of building peace,“ explains Jordan. Roadspeak is the official title for the arts in the community initiative which the East Belfast Mission developed in partnership with five other churches and community groups. The initiative also involves people from the homeless shelter, older adults and others. (for more information log on to www.roadspeak.org).

“What’s going on here is a breath of fresh air,” observes former paramilitary member turned politician, David Ervine. In his early 20s, Ervine spent five years in prison for paramilitary activity. He points to Rev. Gary Mason and the East Belfast Mission team as a new breed who are prepared to go out into the community and get their hands dirty.

“There aren’t many of them,” says Ervine. “Those efforts will bear great fruit.”

East Belfast Mission is banking on it. Helping their community take a chance on peace takes time. Winning the trust of those who have lost faith in institutions, their community and themselves is not without its set backs. In recent elections David Trimble, the Nobel Peace prizing winning Protestant political leader who helped negotiate the Good Friday Agreement for power sharing between Catholics and Protestants, was voted out of office. In his place now sits a much more hard line sectarian politician. The Mission has its work cut out for it. But they’ve always known that.

The Skainos Project is an Advance Special #14698. For more information, visit www.ebm.org.